EternalBlue is a leaked NSA exploit from 2017 that targets Microsoft's SMBv1 protocol and continues to pose a significant cybersecurity threat in 2024-2025, enabling attackers to achieve remote code execution and lateral movement across networks without user interaction, as demonstrated in major attacks like WannaCry and NotPetya, with its persistence driven by poor patching practices and reliance on legacy Windows systems rather than technical sophistication.

Breakdown

EternalBlue, identified as CVE-2017-0144, is a critical remote code execution vulnerability within Microsoft’s Server Message Block version 1 (SMBv1) protocol. The exploit allows unauthenticated attackers to send crafted packets to vulnerable machines over port 445, granting full control of the system. It was developed by the U.S. National Security Agency and exposed publicly in April 2017 by a group known as "The Shadow Brokers". Microsoft released security update MS17-010 a month earlier, but widespread delays in patch adoption left hundreds of thousands of systems open to attack. The vulnerability gained global attention during the WannaCry ransomware outbreak in May 2017, which compromised over 230,000 machines across 150 countries.

EternalBlue enabled the ransomware to spread autonomously through networks, bypassing user interaction and exploiting lateral movement across unsegmented environments. The exploit's ability to propagate without user interaction made it particularly dangerous, highlighting the critical importance of timely patch management. Once released, EternalBlue was rapidly integrated into frameworks, including Metasploit, accelerating its adoption by penetration testers and malicious actors. Its functionality centers on exploiting a memory mismanagement issue in SMBv1, allowing attackers to trigger a buffer overflow and inject executable shellcode. DoublePulsar, another NSA-developed implant also leaked in the same disclosure, is commonly used in tandem to maintain persistent access and execute follow-on payloads. Beyond ransomware, EternalBlue has been incorporated into more complex malware families to deploy crypto-miners, steal credentials, or create footholds in compromised enterprise networks. Threat actors adapted the technique into other variants, including EternalChampion, EternalSynergy, and EternalRomance, each targeting different vulnerabilities in the SMB stack. These variants collectively broadened the attack surface, especially in legacy environments where SMBv1 remained active for compatibility. Despite warnings and available patches, a significant number of systems across both private and public sectors remain unpatched and vulnerable.

EternalBlue’s use has not diminished in the years since its exposure. Following WannaCry and NotPetya, the exploit became a standard part of the toolset for cybercriminals and state-backed threat groups. Malware campaigns, including TrickBot, Retadup, and LemonDuck, have used EternalBlue to automate propagation across internal networks, often in conjunction with credential harvesting and privilege escalation tools. In enterprise environments, attackers often gain initial access through phishing or web-facing services, then use EternalBlue to fan out across unpatched systems. It has also been observed in campaigns linked to nation-state actors in China and North Korea, primarily targeting industries that rely on outdated infrastructure, including Manufacturing, Healthcare, and public utilities. Recent threat intelligence reports from 2024 and early 2025 confirm that EternalBlue is still being used in targeted operations against legacy Windows environments in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe.

Despite newer vulnerabilities surfacing each year, EternalBlue persists due to operational reliance on unsupported systems, budget limitations, and complacency in patch governance. Its continued exploitation is not a reflection of its sophistication but rather a demonstration of how deeply entrenched poor cybersecurity practices remain. The risk associated with EternalBlue is amplified by its ability to facilitate lateral movement without credentials or user interaction, allowing attackers to compromise large portions of a network from a single-entry point. Once inside, adversaries can disable defenses, deploy ransomware, exfiltrate data, or establish long-term persistence. The exploit’s availability in public repositories reduces the barrier to entry for less-sophisticated actors, making it attractive for both opportunistic and targeted campaigns. Organizations operating legacy systems or failing to implement segmentation are particularly vulnerable to cascading impacts. Recovery from EternalBlue-based intrusions often involves costly incident response efforts, system rebuilds, legal liability, and reputational damage. The recurring use of this exploit in real-world campaigns signals a broader issue with global cybersecurity readiness and highlights the risk of continued reliance on deprecated protocols and unsupported systems. EternalBlue remains a case study of how a single leaked exploit can sustain long-term relevance.

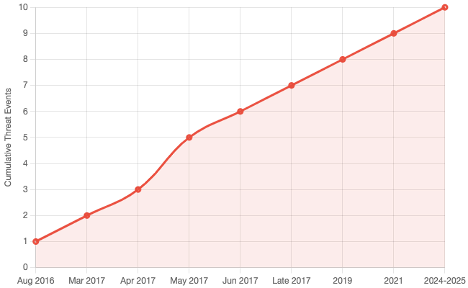

EternalBlue Threat Timeline Evolution

Threat Actor Breakdown

|

The Shadow Brokers |

|

|

Emergence Date |

August

2016. |

|

Attribution |

Believed to be Russian-affiliated or

potentially an insider; exact identity remains unknown |

|

Associated Malware |

EternalBlue, DoublePulsar, DanderSpritz. |

|

Target Industries |

Financial

services, Healthcare, Retail, Automotive, Technology, Government, and Cybersecurity

organizations. |

|

Common Tactics |

Public

release and auction of stolen cyber espionage tools and zero-day exploits. |

|

Recent Activities

|

Leaked NSA-developed cyber tools in 2017,

leading to global malware outbreaks including WannaCry and NotPetya. |

|

Lazarus Group |

|

|

Emergence Date |

May

12, 2017, Linked to the North Korean Lazarus Group. |

|

Attribution |

Believed

to be linked to North Korea's Lazarus Group |

|

Associated Malware |

WannaCry, Ransomware worm encrypting files and

demanding Bitcoin payments. |

|

Targets |

Healthcare,

Government, Telecommunications, Logistics |

|

Common Tactics |

Utilized

EternalBlue for rapid, worm-like propagation across networks |

|

Recent Activities

|

While no major new campaigns have been

observed, WannaCry remains a significant case study in ransomware propagation

and the consequences of unpatched systems. |

|

Sandworm Group |

|

|

Emergence Date |

June

27, 2017 |

|

Attribution |

Attributed

to Russian state-backed actors |

|

Associated Malware |

NotPetya, Wiper disguised as ransomware;

irreversibly destroys data. |

|

Targets |

Primarily

Ukrainian organizations, later spread to global firms through infected supply

chains. |

|

Common Tactics |

Used

EternalBlue and credential harvesting to propagate rapidly within networks. |

|

Recent Activities

|

No ongoing campaigns, but tactics are

still analyzed for critical infrastructure threat modeling. |

|

Indexsinas

(NSABuffMiner) Operators |

|

|

Emergence Date |

2021 |

|

Attribution |

Unattributed |

|

Associated Malware |

Indexsinas (also known as NSABuffMiner) |

|

Targets |

Healthcare,

Hospitality, Education, Telecommunications |

|

Common Tactics |

Exploited

EternalBlue, DoublePulsar, and EternalRomance for lateral movement; deployed

cryptominers and backdoors |

|

Recent Activities

|

Active in 2021; campaigns observed

targeting organizations in the Asia-Pacific region and North America. |

|

Retefe Operators |

|

|

Emergence Date |

2017 |

|

Attribution |

Unattributed;

known for targeting European banking sectors |

|

Associated Malware |

Retefe banking trojan |

|

Targets |

Financial

institutions in Switzerland, Austria, Sweden, and Japan |

|

Common Tactics |

Employed

EternalBlue for lateral movement post-initial infection |

|

Recent Activities

|

In September 2017, Retefe campaigns

incorporated EternalBlue to move laterally within networks, enhancing their

ability to compromise additional systems. |

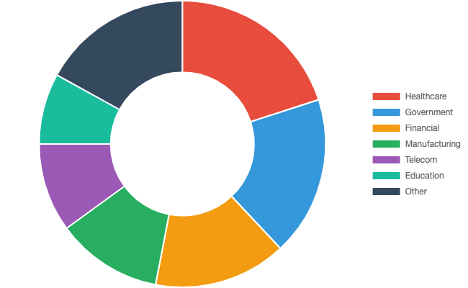

Targeted Industries Distribution

Risk and Impact

Threat actors have repeatedly leveraged EternalBlue in varied and impactful ways, demonstrating its persistent utility long after its initial disclosure. Lazarus Group used it to propagate WannaCry ransomware globally in an automated, self-spreading attack that crippled infrastructure. Sandworm employed the same exploit in NotPetya to enable rapid lateral movement, maximizing destructive impact under the guise of ransomware. Financially motivated groups like LemonDuck and TrickBot adapted EternalBlue to spread cryptominers and banking trojans within enterprise networks, while Retefe briefly incorporated it to extend the reach of credential theft operations. These diverse applications—across espionage, financial crime, and disruption—underscore EternalBlue’s role as a cornerstone exploit in both state-sponsored and criminal toolkits. This ongoing risk is sustained by a global reliance on outdated systems, poor segmentation practices, and the widespread failure to apply critical patches in a timely manner.

Exploit Breakdowns

|

DanderSpritz |

|

|

Emergence Date |

April 2017 (Leaked). |

|

Function |

Modular

post-exploitation framework for managing compromised machines. |

|

Targets |

High-value systems across critical

infrastructure, enterprise, and government networks. |

|

Common

Tactics |

Used for stealthy

surveillance, data theft, and system manipulation. |

|

Recent Activities |

Components discovered during analysis

of attacks that followed the Shadow Brokers’ leak. |

|

DoublePulsar |

|

|

Emergence Date |

April 2017 (Leaked). |

|

Function |

Kernel-mode

backdoor implant allowing arbitrary code execution. |

|

Targets |

Systems already exploited by

EternalBlue or similar vulnerabilities. |

|

Common

Tactics |

Used to maintain

persistent access and deliver secondary payloads. |

|

Recent Activities |

Integrated into modern botnets and used

in campaigns for credential theft and data exfiltration. |

|

EternalBlue |

|

|

Emergence Date |

April 2017 (public release). |

|

Function |

Remote

code execution exploit targeting SMBv1 on Windows systems. |

|

Targets |

Used to gain initial access and propagate

laterally without user interaction. |

|

Common

Tactics |

Public release

and auction of stolen cyber espionage tools and zero-day exploits. |

|

Recent Activities |

Continues to be used in modern malware

campaigns including ransomware and crypto-miners. Newer variants include EternalSynergy,

EternalRomance and EternalChampion. |

|

NotPetya |

|

|

Emergence

Date |

June 27,

2017, Attributed to Russian state-backed actors, likely Sandworm group. |

|

Function |

Wiper disguised as ransomware; irreversibly

destroys data. |

|

Targets |

Primarily

Ukrainian organizations, later spread to global firms through infected supply

chains. |

|

Common Tactics |

Used EternalBlue and credential harvesting to propagate rapidly within

networks. |

|

Recent

Activities |

No

ongoing campaigns, but its tactics are still analyzed for critical

infrastructure threat modeling and destructive malware scenarios. |

Malware Breakdown

|

LemonDuck |

|

|

Emergence Date |

Around 2019, Initially financially

motivated actors, now linked to multiple groups in China. |

|

Function |

Cross-platform

crypto-mining malware with advanced persistence and lateral movement

capabilities. |

|

Targets |

Enterprise Windows environments, cloud

workloads, and IoT devices. |

|

Common

Tactics |

Spreads via

EternalBlue, phishing, brute-force attacks, and exploiting misconfigured

services. |

|

Recent Activities |

Active through 2024, with campaigns

exploiting Exchange vulnerabilities and deploying fileless mining payloads in

hybrid cloud environments. |

|

Retadup |

|

|

Emergence Date |

2017, Linked to French-speaking

cybercriminal groups |

|

Function |

Wormable

malware primarily used for cryptocurrency mining and remote control. |

|

Targets |

Latin America, North America, Europe,

often hitting Healthcare and Education systems. |

|

Common

Tactics |

Propagates

through USB devices and vulnerable Windows systems using tools including

EternalBlue. |

|

Recent Activities |

Was heavily disrupted by a coordinated

takedown in 2019; source code and variants have reappeared in custom crypto-mining

campaigns. |

|

TrickBot |

|

|

Emergence Date |

Late 2016, Initially developed by

Russian-speaking cybercriminals |

|

Function |

Modular

banking trojan evolved into a sophisticated malware delivery platform |

|

Targets |

Financial institutions, Enterprises, Healthcare,

and Educational sectors. |

|

Common

Tactics |

Delivered through

phishing emails, lateral movement using exploits including EternalBlue,

credential theft, and malware deployment. |

|

Recent Activities |

Used in ransomware deployment campaigns

before its infrastructure was disrupted by law enforcement in late 2022;

remnants have since been retooled in smaller-scale operations. |

|

WannaCry |

|

|

Emergence

Date |

May 12,

2017, Linked to the North Korean Lazarus Group. |

|

Function |

Ransomware worm encrypting files and demanding

Bitcoin payments. |

|

Targets |

Global

organizations including Hospitals, Telecoms, Logistics, and Government

entities. |

|

Common Tactics |

Spread via EternalBlue exploit on unpatched Windows systems, with no

need for user interaction. |

|

Recent

Activities |

No major

new campaigns; remains a textbook case of global ransomware propagation and

the consequences of unpatched systems. |

Recommendations

- Disable Legacy Protocols: Fully disable SMBv1 on all Windows hosts through Group Policy or PowerShell to eliminate exposure to EternalBlue and its variants.

- Network Isolation: Isolate legacy or unpatchable systems into dedicated VLANs with no direct routing to production, administrative, or externally facing networks.

- Restrict Lateral Movement: Create and enforce internal firewall rules to block port 445 between endpoint subnets, limiting wormable malware spread through SMB.

- Detect Stealth Implants: Use memory analysis tools including Volatility or Rekall to scan for kernel-level hooks and injected payloads consistent with DoublePulsar activity.

- Validate Patch Coverage: Conduct authenticated scans using updated plugins to identify machines missing MS17-010 or improperly patched against SMB exploits.

Hunter Insights

Based on the report, EternalBlue continues to represent a significant cyber threat despite being publicly exposed in 2017. This NSA-developed exploit targeting Microsoft's SMBv1 protocol remains actively deployed in current attack campaigns, particularly against legacy Windows environments in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe. Its persistence isn't due to technical sophistication but rather stems from poor cybersecurity practices, including delayed patch implementation, operational reliance on unsupported systems, and inadequate network segmentation that allows lateral movement without requiring credentials.

Looking forward, EternalBlue will likely remain relevant in the cybersecurity landscape through 2025 and beyond, particularly targeting industries with outdated infrastructure such as manufacturing, healthcare, and public utilities. We can expect to see continued integration of this exploit into more sophisticated attack chains that combine initial access techniques with EternalBlue for internal propagation. Organizations that fail to implement basic security measures—disabling SMBv1, network isolation, restricting lateral movement, validating patch coverage, and detecting stealth implants—will remain vulnerable to attacks leveraging this nearly decade-old exploit, demonstrating how fundamental security failures continue to provide opportunities for threat actors regardless of technical advancement.